Guest Post: Things I Know?

by Jeff VanderMeer

After 25-plus years in the book world, I will admit I don’t know as much as I should, I suppose. In a way, I don’t want to have Things I Know, because the terrain shifts and you spend some portion of your time adjusting to the current even as you try also think strategically about how you can find the space and opportunity to create what’s most personal to you—and make it a success career-wise.

After 25-plus years in the book world, I will admit I don’t know as much as I should, I suppose. In a way, I don’t want to have Things I Know, because the terrain shifts and you spend some portion of your time adjusting to the current even as you try also think strategically about how you can find the space and opportunity to create what’s most personal to you—and make it a success career-wise.

But I do know a few things from simply being immersed in this world for so long. They tend to apply generally, and I make no claims for them being unique…I just know I sometimes need to remember even what might seem very basic, especially at the start of a new year.

—If you survive and your enemy survives, then over time, your enemy may well become your friend, or at least your cordial colleague. Because so many writers, reviewers, editors tend to fall away over the years, there is a kind of respect that you build up with those in the field who you may have been at odds with, and they with you the longer you’re both around. Don’t under-estimate this effect, and recognize that the reason you may have butted heads in the first place (and survived) is because you share personality traits and other commonalities not at first apparent. I also find that sometimes there is a false impression of intent—for example, a writer who for 10 years thought I hated his writing, even though this was not the case.

—Holding a grudge is counterproductive and has a ripple effect. I know writers who still won’t talk to someone else because of a perceived insult from 20 years ago. The grudge has not only closed them off from a potential friend or a former close friend but also influenced their dealings with others perceived as allies of the other party. I can’t pretend to understand this behavior—there are only four people on my sh*tlist after 25 years and all four did things comparable to putting babies on spikes, but for anything below that threshold…forgiveness is something that can be difficult because it requires swallowing your pride, but it’s important—again, in part because of the ripple effect (even inadvertent punishment of others is wrong) and because people aren’t just one thing. More than once, I’ve found, for example, that crapulous behavior occurred during a time of great stress that the other party wasn’t willing to admit. (Misunderstandings seem to have gotten worse because of the internet, as well.)

—Buying into a personal mythology of hierarchical status can harm your career. It’s one thing to expect respect for your work and experience. It’s quite another to expect demonstrations of your status or to make pronouncements like “I will not attend any conventions at which I am not a guest of honor.” Such pronouncements or ideas are, ironically enough, more likely in writers who have achieved some cult status, whereby they receive daily affirmation from a small but devoted group of fans, which distorts their view of themselves over time. This is also a way of closing off communication and connection, and it winds up harming you. (Excluded from this, of course, are commercial superstars who receive so many invites that there’s no time to do anything else!)

—Buying into the idea of achieving mastery harms your writing. Mastery is an illusion because writing is multi-directional. You can reasonably assume you will over time, if you’re a good writer, achieve “mastery” in certain areas, types of stories, techniques…but even though it could be argued there are a finite number of stories to tell, there are an infinite number of combinations of elements and approaches to create a story. Generally, if a writer thinks they’ve achieved mastery, they’ve simply achieved some success within one area of fiction, which may or may not even signify “mastery” of some element anyway. The point being that every writer eventually enters a decaying orbit, and satisfaction with one’s mastery of writing is one sign of that process reaching its end stages. At the very least, a plateau may have been reached. (For some, there’s no harm in this–some writers basically tell the same story their entire lives, and throughout their careers they are simply seeking to tell that story more and more perfectly.)

—Fear and taking the short-term view will harm not just your career but your creativity. Conversely, taking chances while keeping the long-term in mind will often reward you. But the important thing here is beating the fear. Even writing itself is often about beating the fear–evading the fear that comes with the editorial mind-set, which can rob you of the confidence to write. In the broader sense, it’s fear that makes us not push outside of our comfort zones. It’s fear that tells us we’re not worthy of an opportunity. It’s fear that tells us this new thing isn’t something we can actually accomplish. Jumping in with both feet while being aware of the long-term effects of what you’re doing is so important. Saying yes is so important. As important? Don’t fall into patterns of paranoia and bitterness. Something is always going to go wrong in your career. There’s no getting around that. You can lose yourself in circles of why that turn your world into a place where you only see the negative. This just feeds the fear more, and gives you more excuses to not do something.

—Friendship is more important than career advancement. Even beyond the obvious reasons why you shouldn’t screw over your friends, the practical, cynical truth is that very few things that seem important at the time will turn out to be important over time. (I’m not someone who screws over friends anyway—it’s more that I get so busy, I wind up not having time for old friends as much as I should.)

—Friendship is not as important as doing the right thing. As in most fields, writers tend to be friends with fellow writers and editors, among others connected to the book field. You’re not doing your friend any favors by sugar-coating a critique, favoring them without due cause in a reviewing or during awards season, or any other situation, etc.

—Paying it forward and being open with information is important for the long-term health of the book culture. It’s a myth that anyone makes it on their own. You may make it despite the odds, but you still had help along the way—people sympathetic to what you wanted to do. The most positive thing you can do is return is help other people when you can. The impulse to hoard information or to not be of use usually comes from the impression that you yourself may be ill-served by doing so. But in actual fact, this is rarely so. The connectivity and communication you engage in usually results in all kinds of creative collaborations and opportunities over time. And I don’t mean in a cynical “you owe me way,” but just naturally as a result of being willing to be open.

—A sense of humor and an appreciation of the absurd are a huge plus. Without a sense of humor, I’m not sure how a writer survives, given that humor is so important to taking a long-view approach (time plus tragedy equals humor). A healthy appreciation for the absurd is an additional survival attribute that helps to put things in perspective.

•••

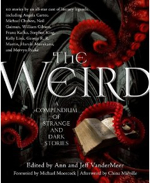

Jeff VanderMeer has had novels published in fifteen languages, won multiple awards, and made the best-of-year lists of Publishers Weekly, the San Francisco Chronicle, the LA Weekly, and many others. His award-winning short fiction has been featured on Wired.com’s GeekDad and Tor.com, as well as in many anthologies and magazines, including Conjunctions, Black Clock, and in American Fantastic Tales (Library of America). His nonfiction has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, the Washington Post, The Huffington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and Salon.com. With his wife Ann, he launched WeirdFictionReview.com, which has become one of the world’s most robust sources for fiction and nonfiction related to the weird. Their latest offering is The Weird, a 750,000-word anthology covering 100 years of weird fiction.

Jeff VanderMeer has had novels published in fifteen languages, won multiple awards, and made the best-of-year lists of Publishers Weekly, the San Francisco Chronicle, the LA Weekly, and many others. His award-winning short fiction has been featured on Wired.com’s GeekDad and Tor.com, as well as in many anthologies and magazines, including Conjunctions, Black Clock, and in American Fantastic Tales (Library of America). His nonfiction has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, the Washington Post, The Huffington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and Salon.com. With his wife Ann, he launched WeirdFictionReview.com, which has become one of the world’s most robust sources for fiction and nonfiction related to the weird. Their latest offering is The Weird, a 750,000-word anthology covering 100 years of weird fiction.

This post first appeared on Jeff VanderMeer’s blog, Ecstatic Days. Photo by Keyan Bowes.