A Valentine’s Day Guest Post: Tentacle Sex

After reading, Kij Johnson‘s Nebula Award-Winning story, “Spar,” do you find yourself longing for more tentacle action? Sure there’s H.P. Lovecraft, H.G. Wells, Jules Verne, C.L. Moore, and hundreds of other writers who’ve had literary dalliances with calamari, but this Valentine’s Day, we invite you to consider the wellspring. It’s time to put on some Barry White, take a bubble bath, and cuddle with your favorite cuttlefish. -Ed.

•••

Tentacle Sex

by PZ Myers

Doesn’t everyone just love cephalopods? I find them to be a fascinating example of a body plan radically different from our own, the closest thing to a truly alien large metazoan on our planet. I try to keep my eyes open for new papers on cephalopod development, but unfortunately, they are rather difficult to study and data is sadly thin and tantalizing.

Doesn’t everyone just love cephalopods? I find them to be a fascinating example of a body plan radically different from our own, the closest thing to a truly alien large metazoan on our planet. I try to keep my eyes open for new papers on cephalopod development, but unfortunately, they are rather difficult to study and data is sadly thin and tantalizing.

I just ran across a pair of papers by Jantzen and Havenhand (2003a, b) on squid mating. That’s close enough to development for me!

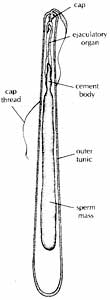

First, let me explain a few general features of squid sex. Males produce elaborate spermatophores, illustrated to the left, which are complex packages of sperm. Huge numbers of sperm are stored centrally (1010 sperm, in some species), enclosed in a discharge mechanism that is triggered osmotically or mechanically—basically, it’s like those joke peanut cans that fling out a springy surprise when opened. Squid sex is a process of passing one of these clever novelty items to a female, where it will then go sproing when she lays some eggs.

Male squid do not have a penis. Instead, they have a pouch that opens into the mantle cavity, called Needham’s sac, where spermatophores are stored, and they have a specially modified tentacle, the hectocotylus, which is used to reach into the sac, scoop out a spermatophore, and and place it inside the buccal or mantle cavity of the female. In some cephalopods, the end of the hectocotylus snaps off and remains imbedded in the female.

Simple, hey? Of course, in the real world, it becomes much trickier, more exotic, and beautiful.

The first paper by Jantzen and Havenhand (2003a) describes the body patterns of squid courting and mating in their spawning grounds in South Australia. Cephalopods are famous for their ability to change color and pattern, and they give those capabilities a workout while trying to signal mates. They go through specific postural and chromatic activities that the authors describe; the body poetry of affectionate squid involves “rigid arms”, “upward curls”, and “peristaltic arm flares” while displaying “golden epaulettes” or “stitchwork fins” or “iridiscent sclera”. It’s lovely stuff. It makes my habit of picking out a clean shirt before going out on a date look rather pathetic—I’d have to take up ballet and gymnastics and start wearing luminescent make-up and glo-tubes if I want to keep up.

The second paper (Jantzen and Havenhand, 2003b) is more of a Kama Sutra of squid intercourse. Squid have a preferred position, illustrated below, in which the male swims upside-down above the female, and deftly scoops out a spermatophore which he deposits in the females buccal cavity, while the male is flashing “mantle margin stripe”, “dark arm stripes”, and “fin stripes”, and she is showing off “white dorsal stripes”, “golden epaulettes”, and “rigid arms”.

Six-frame sequence of “male-upturned mating” behavior in Septoteuthis australis. The male (top) swims into position over the female (bottom, a). The male then rotates into the upside down position (b) and gathers spermatophores (Sp) from the funnel with the left 4th hectocotylized arm (c). The hectocotylized arm then moves down the right 4th arm that is positioned in the buccal area of the female (d) and and deposits spermatophores in this area (e). Copulation is complete, and the male rotates back to the normal swimming position (f). Total time elapsed = 3s.

__________________

Squid also like a little variety. With much lower frequency, they try head-to-head matings, or with the female on top (“male-parallel”).

Percentage of all matings of each of the four mating types (male-upturned, head-to-head, male-parallel, or sneaker) identified in Sepioteuthis australis, with illustrations of the three mating types between paired individuals.

___________

Percentage of all matings of each of the four mating types (male-upturned, head-to-head, male-parallel, or sneaker) identified in Sepioteuthis australis, with illustrations of the three mating types between paired individuals.

A particularly interesting case is sneaker mating. In these attempts, a male would coast up to a courting pair and attempt to flick in one of his spermatophores. Sometimes, while the sneaker was trying to make his deposit, he’d display the typical paired female body patterns of “dorsal white stripe”, “golden epaulettes”, and “rigid arms”; the females did not seem to appreciate these devious intrusions, and would most often jet away. The sneaker males were not only unpopular, but sloppy, and would splatter spermatophores onto the female’s head, arms, or mantle.

Some of the cool features of this animal system are the opportunities to study male competition and mating strategies. The fact that females are repulsed by sneaker males strongly suggests that female selection is important. And they are gorgeous to watch.

Jantzen TM and Havenhand JN (2003a) Reproductive behavior in the squid Septoteuthis australis from South Australia: Ethogram of reproductive body patterns. Biol. Bull 204:290-304.

Jantzen TM and Havenhand JN (2003b) Reproductive behavior in the squid Septoteuthis australis from South Australia: Interaction in the spawning grounds. Biol. Bull 204:305-317.

•••

PZ Myers is a biologist and associate professor at the University of Minnesota, Morris. He is the author of the blog Pharyngula, declared by Nature as the best blog written by a scientist.

PZ Myers is a biologist and associate professor at the University of Minnesota, Morris. He is the author of the blog Pharyngula, declared by Nature as the best blog written by a scientist.

This post originally appeared online at Pharyngula.