by Tim Susman

The first time I tried to write a comic book script, I had no guidance about what a script looked like, but I’d read comic books and graphic novels. So I wrote up my idea for a four-to-five-page story and sent it to the editor. He sent it back with a gentle note that read, paraphrased, “This is about twenty pages worth of material.”

I was taken aback because I’d separated it into five pages. But when I looked more closely at it, I saw what he meant. I’d crammed way too much into each of those five pages. With help from the artist I was working with, I pared it down, and we got the story to the required length (with some necessary but painful cuts).

Part of the problem was—and is—that there is no definitive template for comic scripts like there is for screenplays. At the end of this post are links to comic script archives; I suggest browsing them to see how established, published writers have tackled the problem. What I’ll cover here are the basics to keep in mind when writing a comic script: collaboration, layout, and dialogue.

Collaboration

If you are lucky enough to have an artist assigned to work on the project with you, your job becomes much more manageable. The comic script is a list of instructions for the artist, and any artist can tell you how best to write instructions for them. My experience has been that artists produce their best work when they have some kind of creative input, so I suggest that your comic script leave room for the artist to bring their creativity to the project. Alan Moore famously wrote highly detailed scripts, each panel meticulously described in immense paragraphs, but even in those details, he would include several alternatives and then write, “the options are there, so just do what you want,” allowing the artist to make some choices about the image. Your artist will create the look of your comic, so leave them room to interpret your words in their style–just as in writing a screenplay, where you can tell the actor and director the character’s mood, but leave the interpretation on screen up to them.

Layout

If you don’t have an artist assigned, the layout of your comic script is the biggest hurdle for a new writer. Comics (you are probably aware) are broken down into pages, and pages are broken down into panels. Most writers delineate these with “PAGE:” and “PANEL:,” but as I wrote above, there is no standard format; please browse the examples linked below. In general, it’s helpful to think of the scenes of your story in units of pages—and each scene is fewer pages than you might think.

Whether you dictate the panel layout within the page is up to you. Most scripts I’ve seen include at least a breakdown by panel, often allowing the artist to decide the relative sizes if it’s not one of the standard comic page layouts. On occasion, a writer might free-form a page and allow the artist to do the breakdown; they might also go in the other direction and specify the precise layout of the page. Some artists prefer the freedom to play with layout; others might like the defined structure. Once you have an artist to work with, you may (likely will) have several conversations clarifying your vision and incorporating the artist’s ideas.

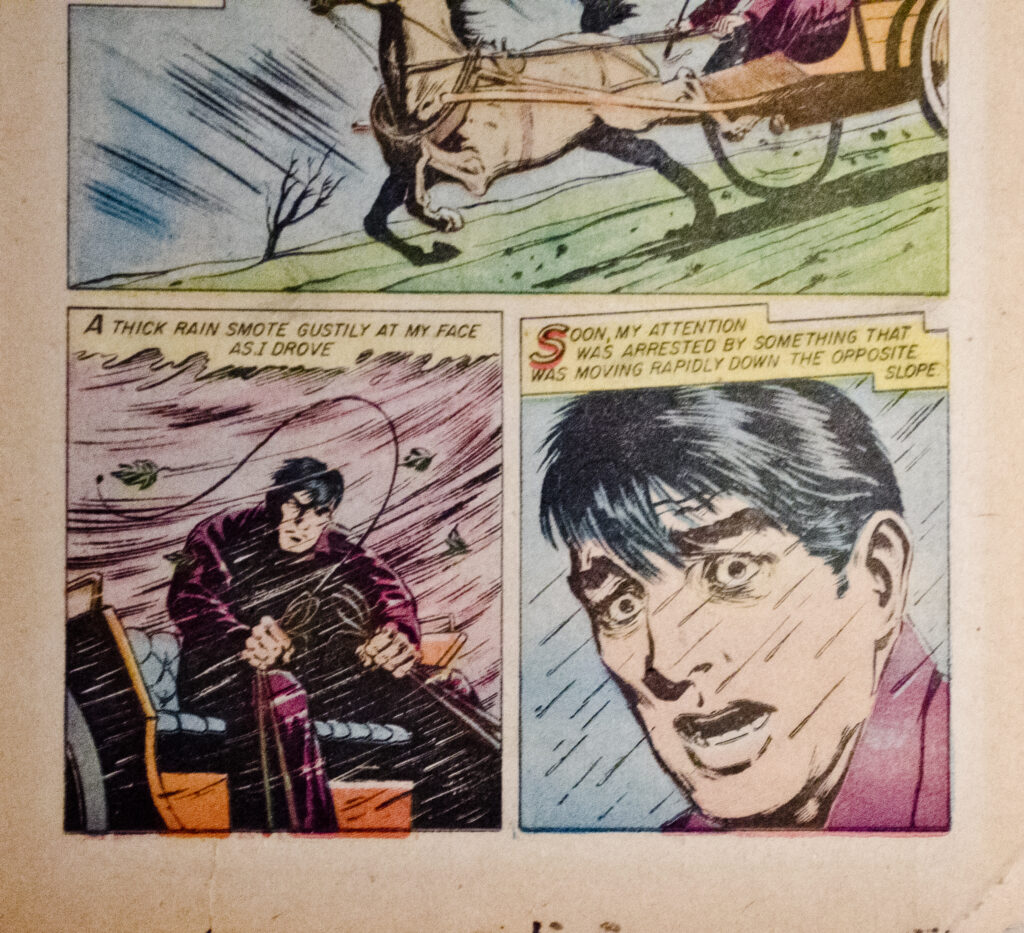

My mistake in the above example was to try to write out each moment of the scene panel by panel; that’s not how most comics are written. If you want to take advantage of the comics medium, decide which moments in your scene are crucial. Make a panel for each of those moments and allow the reader to interpolate the rest. Scott McCloud in his seminal work Understanding Comics talks about the importance of the spaces between panels in a comic (gutters), how “closure” (the way we intuit the whole of something from seeing parts of it) allows the reader to build a more complex story than just what’s on the page.

“War of the Worlds – Classic Comics page – Space A Journey to Our Future – Museum of the Rockies – 2013-07-08” by Tim Evanson is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

You can also control the pace of the story through layout. The reader reads at a more or less constant rate, so you can speed up the story or slow it down by the content of each panel. Quick transitions that move the story along will make it feel more dynamic (think of any superhero fight scene); slower transitions will force the reader to slow down (think of a sequence of panels lingering on a character as their expression slowly changes; we are with them in the moment of understanding). When I said “key moments only,” that doesn’t mean you have to jump around in every scene. In a fraught conversation, every line of dialogue might be a key moment.

Dialogue

Dialogue in comic scripts has constraints unique to the form. All the words you assign to the characters in a panel have to share space with the images of the characters and the background, both of which also convey important information to the reader. Long speeches sometimes happen in comics, but the shorter you can make your dialogue, the better. You can make up for information not revealed in dialogue by describing character expressions and poses, and by putting information into the background. Comics are a unique combination of the written and visual arts; the best comics take advantage of both.

Comic Script Archives

Below, as promised, are some archives of comic scripts:

- The Comic Book Script Archive

- Scripts & Scribes: Sample Comic Book Scripts

If you don’t have an artist to work with, study a few of these, considering the above rules. And remember: The only “right” way to write a comic script is the way that allows your artist to produce a comic from your shared vision.

Explore more articles from THE COMICS PANEL

Award-winning author Tim Susman began his writing career while pursuing degrees in chemical engineering and international business at the University of Pennsylvania. He later earned a master’s in zoology from the University of Minnesota, where he worked with primatologist Jane Goodall. After relocating to the San Francisco Bay Area, he embraced writing full-time. Tim co-founded Sofawolf Press, where he edited several comic stories and graphic novels. His stories have appeared in Apex and Lightspeed, and he’s authored 40+ novels and several published comic stories.

Award-winning author Tim Susman began his writing career while pursuing degrees in chemical engineering and international business at the University of Pennsylvania. He later earned a master’s in zoology from the University of Minnesota, where he worked with primatologist Jane Goodall. After relocating to the San Francisco Bay Area, he embraced writing full-time. Tim co-founded Sofawolf Press, where he edited several comic stories and graphic novels. His stories have appeared in Apex and Lightspeed, and he’s authored 40+ novels and several published comic stories.