by Guy Windsor

All the best stories end with a sword fight, and there are usually many sword fights leading up to the climactic duel between the hero and the villain. It’s important to get these right because, if you kick your reader out of the world you’ve created for them with a confusing, unbelievable, or just plain wrong bit of fight description, you’ll lose the tension you’ve worked so hard to generate.

My top three tips for fantasy and historical fiction writers are:

1. Do your research (or use other people’s).

2. Avoid jargon.

3. Run through the fight in the real world.

Do Your Research (or Use Other People’s)

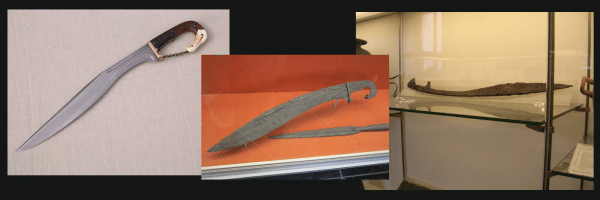

Base your characters’ weapons and fighting styles on historical sources. Every culture has produced something sword-like for purposes of combat and status. We have archaeological and historical records of swords made from wood, glass, stone, copper, bronze, iron, and steel. The Aztec macuahuitl is a wooden sword with obsidian glass chips bonded to the edges. The ancient Egyptians fought with hooked bronze swords called khopesh. Australian Indigenous people made sharp-edged wooden swords. There are the Chinese dao and jian, the Japanese katana, the ancient Greek makhaira, the Roman gladius, Indian pata, Viking sword, arming sword, longsword, rapier, sidesword, smallsword, saber, backsword, and on and on.

Every culture that made swords had methods of using them that were at least as sophisticated as the weapon itself. We know this from archaeological finds, the historical record of descriptions of fights, and, starting in the 1300s, detailed treatises on sword fighting styles.

There is no need for you to be an expert in any of these weapons. But you can base your characters’ armory on existing weapons (the way the lightsaber is based on the knightly longsword) and find out how their weapons would have been used. There are legions of people figuring it out for you already and publishing their findings (like me and my colleagues).

There are two main approaches for figuring out the systems: reconstructive archaeology and historical research.

Reconstructive archaeology is the process of reconstructing the weapons (or other tools) and figuring out by trial and error how they were likely used. In the case of bronze swords, examining the notches on existing blades and comparing them to notches created on new blades by various cuts, parries, and so on, gives us an idea of how these weapons interacted with each other.

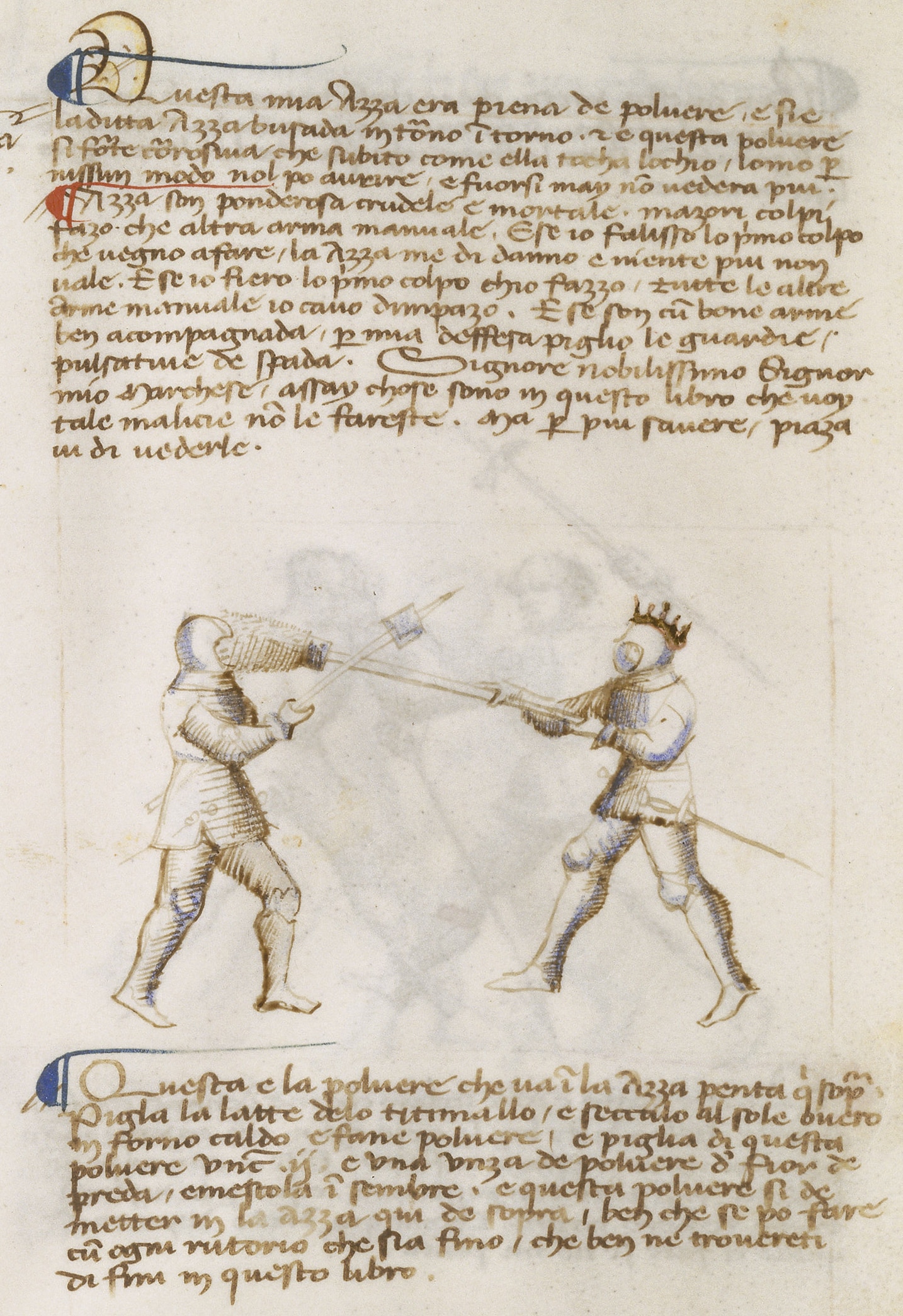

Historical research looks to the written record. From the 1300s onwards, we have manuscripts that go into extraordinary depth and detail about specific combat systems, such as Fiore dei Liberi’s Il Fior di Battaglia (ca. 1400), which tells you everything you could want to know about knightly combat, including the dastardly trick of filling your pollax head with blinding powder.

We have hundreds of sources from the 16th century onwards, and fencing masters kept writing new ones until the present day. Many of those sources and masters have students devoted to reconstructing their art. Pick a weapon for your character, modify it to suit your story, then find someone who is practicing with it and ask for advice.

Avoid Jargon

Most readers don’t know a macuahuitl from a makhaira, and they didn’t pick up your novel to be taught a lesson; they picked it up to be entertained. The pitfall of doing your research is that you let too much of it leak out onto the page. Any time your reader comes across a word they don’t know, their mind will skip over it, or they’ll get bogged down. Neither one is good. You have been immersed in this world for thousands of hours, so you know it better than they do. If you do have a special word for something (Lucas’s lightsaber, Tolkien’s Anduril, Bujold’s plasma arc), make it clear from the context what it is and how it works.

Most people know what a rapier is, more or less. But a makhaira? This sword is famous, but nobody has heard of it. Alexander the Great fought at Gaugamela with the makhaira given to him by Kition, King of Cyprus. When the Apostle Peter used a sword to cut the ear off poor Malchus in the Bible (John 18:10), it was, in the original Greek, “μάχαιρα”—“makhaira.” When it is written in the King James version of the Bible that Jesus said, “I came not to send peace, but a sword,” (Matthew 10:34), it is again “makhaira” in the original Greek.

But put that into a novel, and you are guaranteed to send 99% of readers out of the zone and off to a dictionary, where they will discover that the makhaira was popular from about 400 BCE, and was a forward-curving sword, good for cutting, that Xenophon recommended for use by cavalry in place of the straight-bladed xiphos.

Run Through the Fight in the Real World

This does not have to be done at speed with sharp swords. You can do it with a pen in each hand, at your desk. But make sure that the scene you are describing works in practice, not just in your head. If you are avoiding jargon, you will find this easier because you can leave space for the reader to imagine the action.

“The villain attacked with a flurry of thrusts and cuts, beating our hero back against the castle wall” is better than listing the specific actions she used. When the specific action matters (if you want to use a dastardly technique to indicate a villainous character, for instance), then block it out move-by-move to make sure the sword doesn’t magically pass through a body part without hurting it. Be very sparing with this—most readers don’t want to work through the specifics.

It’s Your Book

I hope this advice is useful. Do your research, avoid jargon, and run through the fight in the real world. But it’s your book, not mine, so take my rules with a pinch of salt!

Explore more articles from WORLDBUILDING

Consulting Swordsman Dr. Guy Windsor is renowned as a teacher and researcher of medieval and Renaissance martial arts. He has been teaching professionally since founding Swordschool in Helsinki, Finland, in 2001. Awarded a PhD by Edinburgh University for his seminal work recreating historical combat systems, Guy has written numerous books on swordsmanship, such as The Medieval Longsword, The Medieval Dagger, Swordfighting for Writers, Game Designers and Martial Artists, The Duellist’s Companion, and many others.

Consulting Swordsman Dr. Guy Windsor is renowned as a teacher and researcher of medieval and Renaissance martial arts. He has been teaching professionally since founding Swordschool in Helsinki, Finland, in 2001. Awarded a PhD by Edinburgh University for his seminal work recreating historical combat systems, Guy has written numerous books on swordsmanship, such as The Medieval Longsword, The Medieval Dagger, Swordfighting for Writers, Game Designers and Martial Artists, The Duellist’s Companion, and many others.

He has also created a huge range of online courses, covering medieval knightly combat, sword and buckler, rapier, and related topics. Now, Guy splits his time between researching historical martial arts, writing books, and creating online courses, teaching students all over the world. He hosts the popular historical martial arts podcast The Sword Guy, with guests including Steven Pressfield and Neal Stephenson. His latest book is Swordfighting for Writers. You can find him and his work online at swordschool.com.