by Rosemary Jones

Pulp magazines ruled the newsstands in the early 20th century. They provided readers with science fiction and fantasy, as well as other genre stories, for a low cost. Millions of copies were sold. Until one man decided he didn’t like the pulps and invented the mass market paperback, which would become the leading cheap book format by the 1950s.

Or at least that’s how the story goes. A plaque installed at the Exeter St Davids station in 2017 commemorates the moment Sir Allen Lane looked over the fiction available for sale at the newsstand and couldn’t find anything worth reading on his train trip. Wanting a “good book” at a pulp price, he came up with the idea of the Penguin paperback featuring quality fiction and nonfiction reprints. Beginning in 1935, the British publisher sold exclusively standardized paperbacks for sixpence each.

Lane started in publishing at Bodley Head, the prestigious British publisher founded by his uncle, John Lane. A champion of James Joyce and other literary stars of the 1920s, Lane was ideally positioned to secure reprint rights. Penguin began as an imprint of Bodley Head, but Lane and his brothers quickly spun it off as its own entity.

Penguin did not use the famous train station story in their book about their 21st anniversary, published in 1956. Instead, the author, Sir William Emrys William CBE, notes that a number of low-priced reprints already existed in a paperbound format, but “many of them dealt only in the more expendable kind of fiction.”

Lane’s innovation, according to Williams, was to find a way to bring the best literature and nonfiction to a larger mass of readers in the economically tough times of the 1930s.

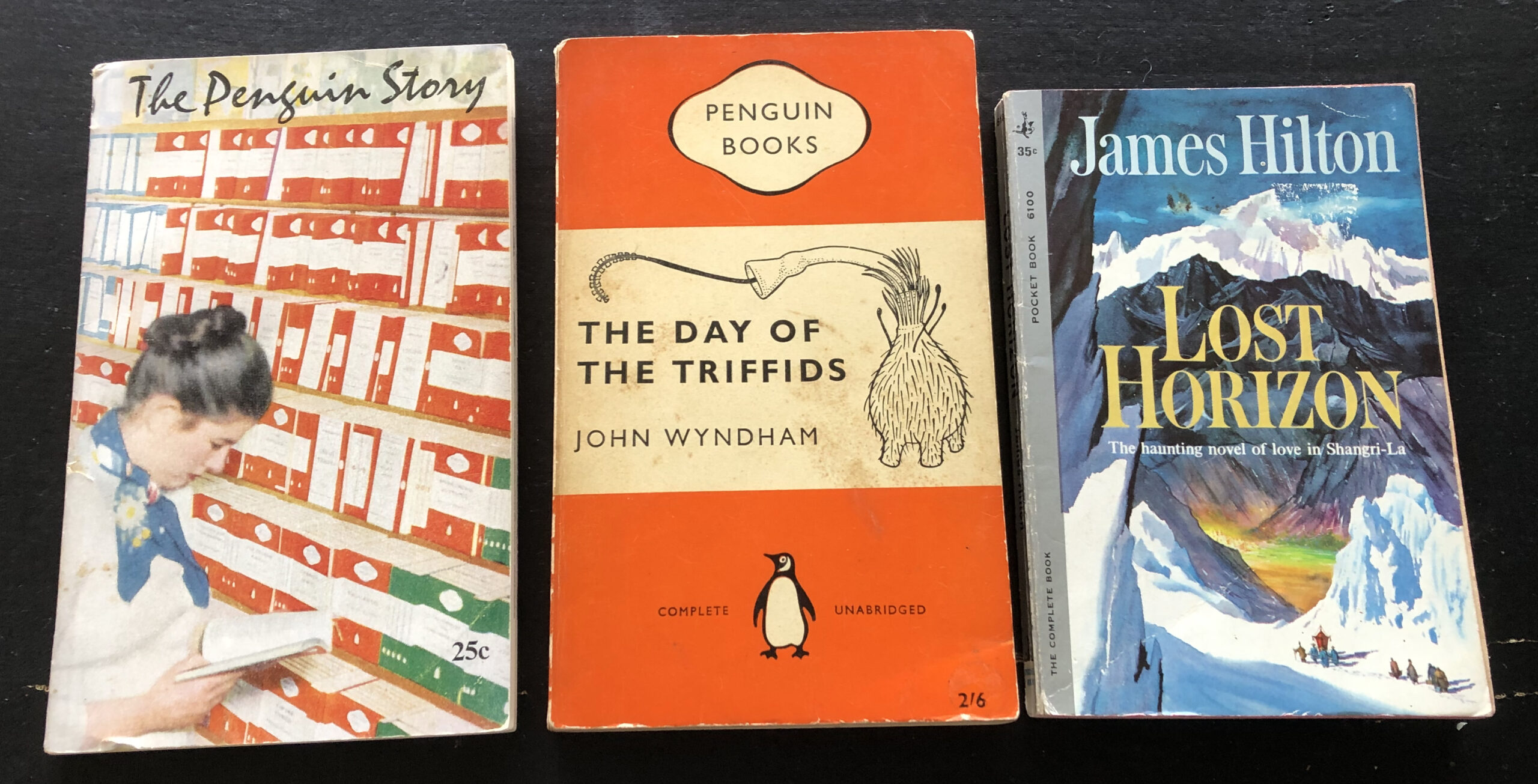

Besides the low price, Williams argues that Penguin’s other advantage over its paperbound predecessors was to create attractive books. Certainly, the Penguin paperbacks provided a great example of branding from the start. Rather than having individually designed covers, all Penguins looked alike. Fiction had orange-and-white covers with the Penguin name in a cartouche over the title in the top orange band. The book’s title and author’s name were set in Gill Sans font in the middle white band, and a penguin logo was printed in the middle of the bottom orange band. All early Penguins were the same size too: 7 ⅛ inches tall by 5 ⅛ inches wide. By 1937, the venture was so successful that a flock of variations took flight from the publisher: Puffins, Pelicans, and King Penguins. The main colors now included orange (general fiction, including science fiction), green (mysteries and crime fiction), blue (biographies), and cerise (travel and adventure).

Very quickly, readers began to associate Penguins with color-coded mass market paperbacks rather than flightless birds. The fact that Penguin numbered all their paperbacks appealed to collectors almost from the beginning. The idea of “numbering” appeared on earlier softcover books issued by other European publishers, such as Tauchnitz Editions, and would be used by paperback publishers for decades.

Williams’s history ignores The Albatross Press in Germany, which launched before Penguin and used a very similar format, complete with color-coded titles. Publishing English language reprints for Europeans, the Albatross books were remarkably successful, but the company was gone by 1939. Arguably, it was Penguin and their American counterpart Pocket Books that truly made the paperback “mass market” by selling to millions of readers in the 1940s and inspiring numerous other publishers to get into the paperback business.

Pocket Books Follows Penguin

In the United States, Pocket Books tested their first pocket-sized paperback in 1938, The Good Earth by Pearl Buck, by selling it only in the New York area. They went into mass production the next year with Lost Horizon by James Hilton, an award-winning romantic fantasy adventure, and nine other titles. Their books sold for 25 cents each for two decades. As Pocket recounts their history in a later edition:

“In June 1939, [Lost Horizon] became the first title in the first list published by Pocket Books, Inc., the firm which began the ‘paper-bound revolution’ in modern publishing. For twenty-one and a half years, it remained Pocket Books #1 at 25 cents, through forty-six printings, totalling nearly 2,000,000 copies. Finally, in 1961, it, too, yielded to the increases in prices and became Pocket Book #6100 at 35 cents.”

Penguin Books Ltd. also opened a branch in the United States around the same time. This division quickly brought together Ian Ballantine, who would become a prominent name in science fiction paperback publishing, and Kurt Enoch, one of the Albatross Press founders, who had fled Nazi Germany with his family. The pair would eventually part company with Penguin to head their own companies, forming Bantam Books (Ballantine) and New American Library (Enoch).

Paperbacks Boom in the 1940s

Despite the hardships of World War II, the early 1940s saw a boom in the demand for paperbacks. Not only were those cheaper for the average citizen, but the format was ideal for soldiers to carry in their pockets. Publishers received government contracts to supply books to the troops. Penguin cut a deal to print exclusive editions for Canadian troops in return for Canadian paper, helping them achieve even greater quantities of books despite Britain’s shortages.

Pocket and other American publishers participated in the Victory Book Campaign, sponsored by the American Library Association, the Red Cross, and the USO. Readers were urged to donate books by dropping them off at the nearest public library because “Our Boys Want Books,” as the first page of a 1942 Pocket Book proclaims. American publishers also gave away books, shipping an estimated 122 million books of all types to the troops around the world.

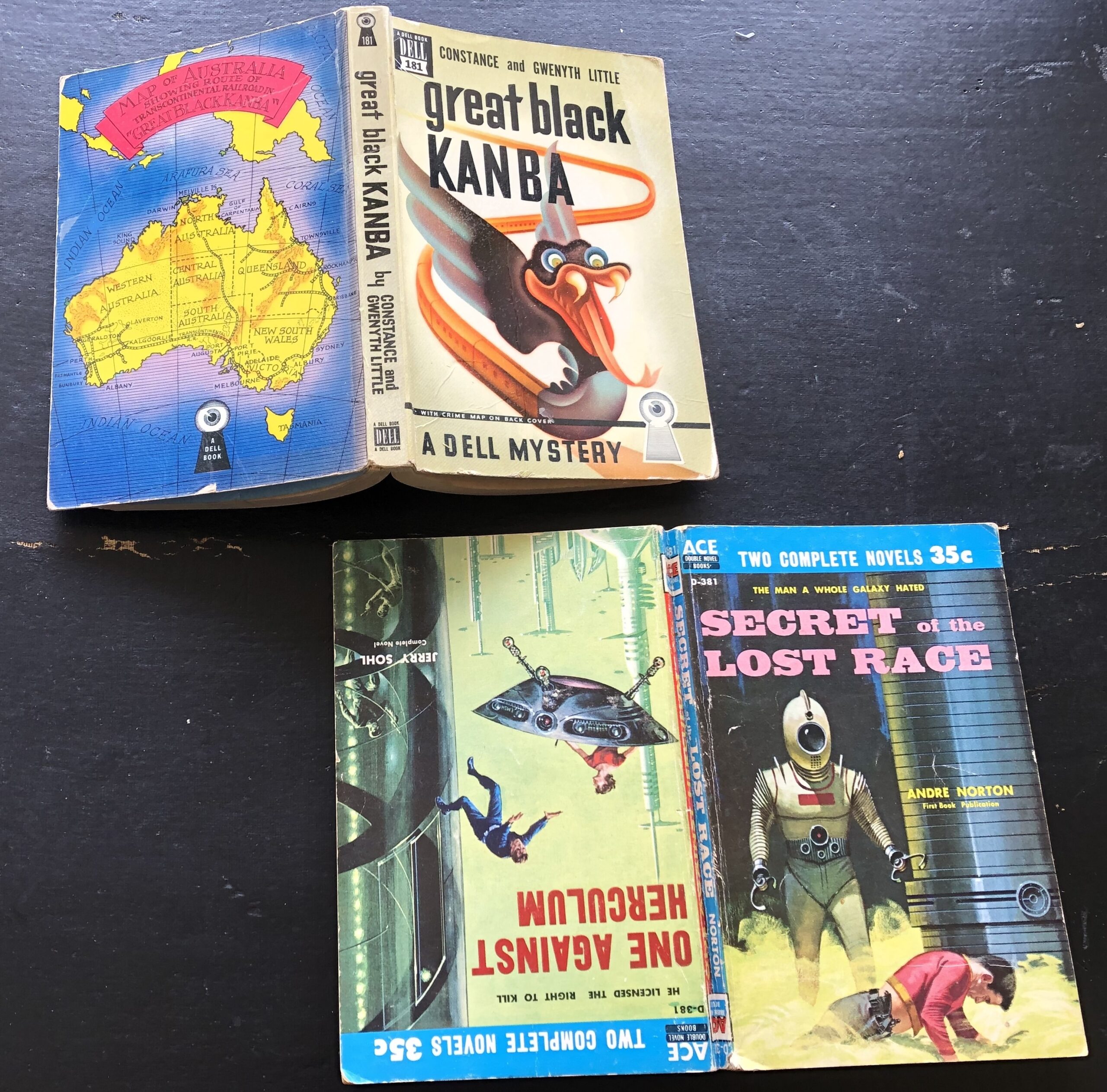

Pocket Books was quickly followed by Avon, Dell, and Pyramid, among others. Many of these copied Pocket’s small size, 6 ½ inches tall by 4 ¼ inches wide. Unlike Penguin, the American rivals took full advantage of the newest color printing and lamination techniques to produce the full-color illustrated covers desired by sellers. Particularly striking were the Dell Mapbacks, which provided a stylish illustration on the front and a map of where the story took place on the back.

Eventually, the American mass market paperback size grew to 7 inches tall and 4 ¼ inches wide, designed to fit on standardized racks or spinners in retail spaces.

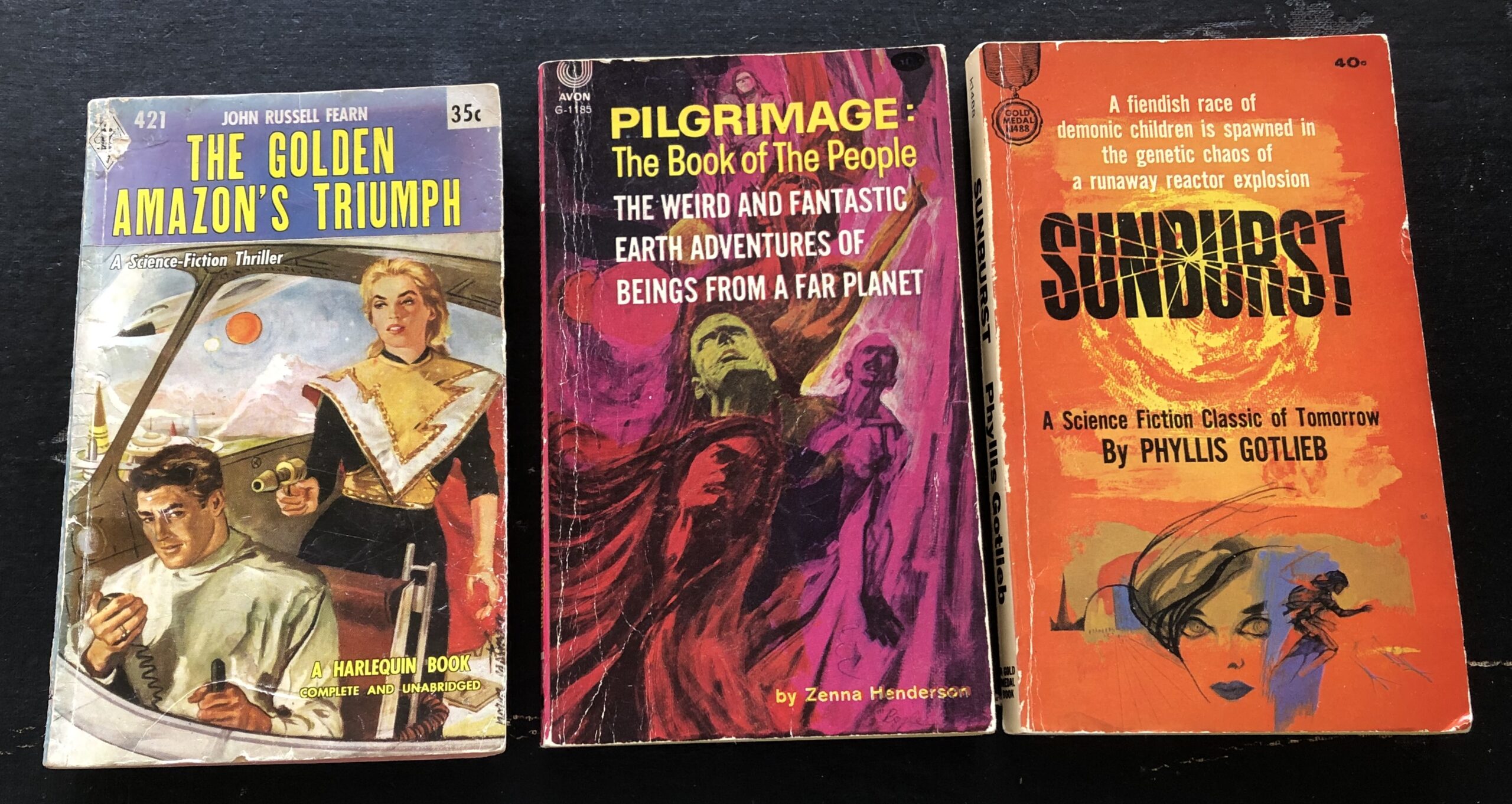

The Canadian Harlequin Books began as a paperback reprinter of various genres in 1949, including “science-fiction thrillers.” The company switched to focusing exclusively on romance in the 1960s. Harlequin also parlayed a specific brand cover style and distribution through non-bookstore outlets into financial success.

Paperback Originals and Ace Doubles

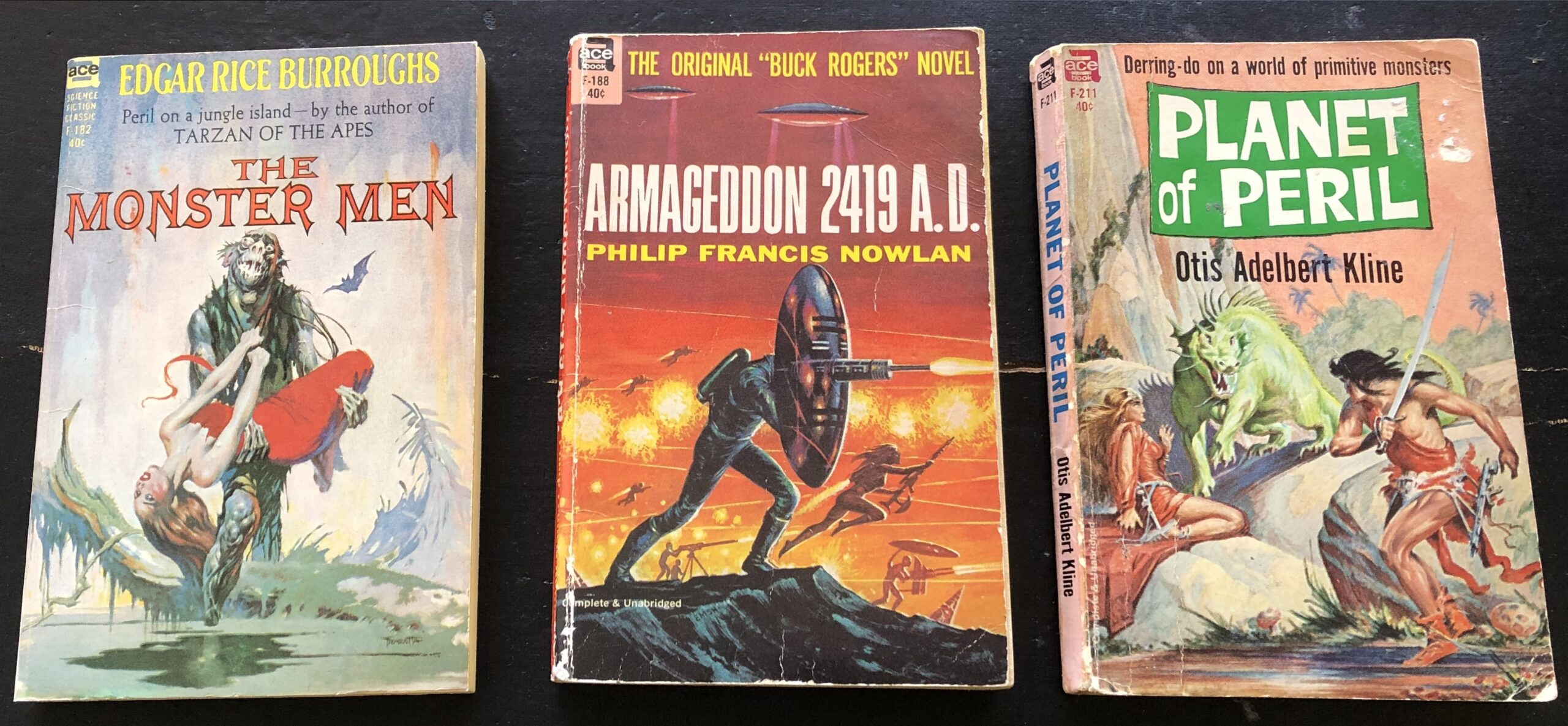

Nearly all paperback houses published some science fiction or fantasy, but mostly editions of classic authors like H.G. Wells or reprints of hardcover bestsellers. In 1949, Fawcett launched Gold Medal paperbacks, which published “originals” written for the line, including science fiction.

Another source of new science fiction was the Ace Double, started in 1952 by Ace Books. Early copies sold for 35 cents. Each double contained a reprinted novel and an original novel arranged in an innovative flip format with two front covers. Ace also reprinted pulp favorites with fantastical covers and frontispiece illustrations. By the end of the 1950s, fantasy and science fiction accounted for the bulk of Ace paperbacks.

Tolkien Says Buy Authorized Editions

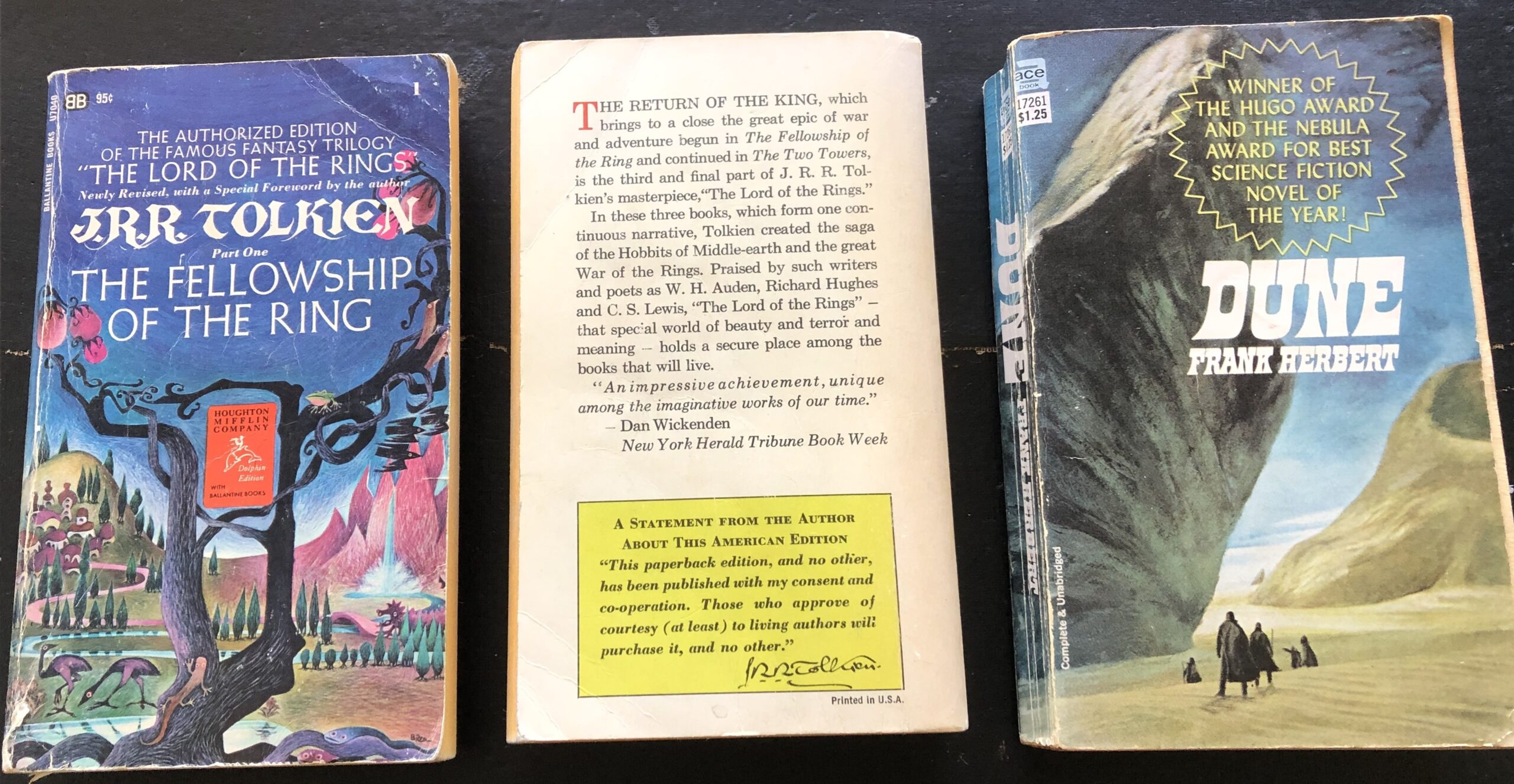

Also in 1952, Ian and Betty Ballantine created Ballantine Books and quickly acquired a fantasy and science fiction catalog. Ballantine and Ace competed for the genre’s authors and readers, including a Lord of the Rings clash in 1965. Ace reprinted the trilogy without the permission of the still-living author due to a loophole in copyright law. Ballantine published an “authorized” edition with a famous back cover note from J.R.R. Tolkien:

“This paperback edition, and no other, has been published with my consent and co-operation. Those who approve of courtesy (at least) to living authors will purchase it, and no other.”

Ace dropped their Tolkien books after only one printing, copyright law was amended, and Ballantine triumphed with a massive fantasy bestseller. However, Ace scored an equal mega-hit in 1967 when they picked up the paperback rights for Dune by Frank Herbert from Chilton, a publisher of car repair manuals.

The 1970s Bring More SFF Imprints

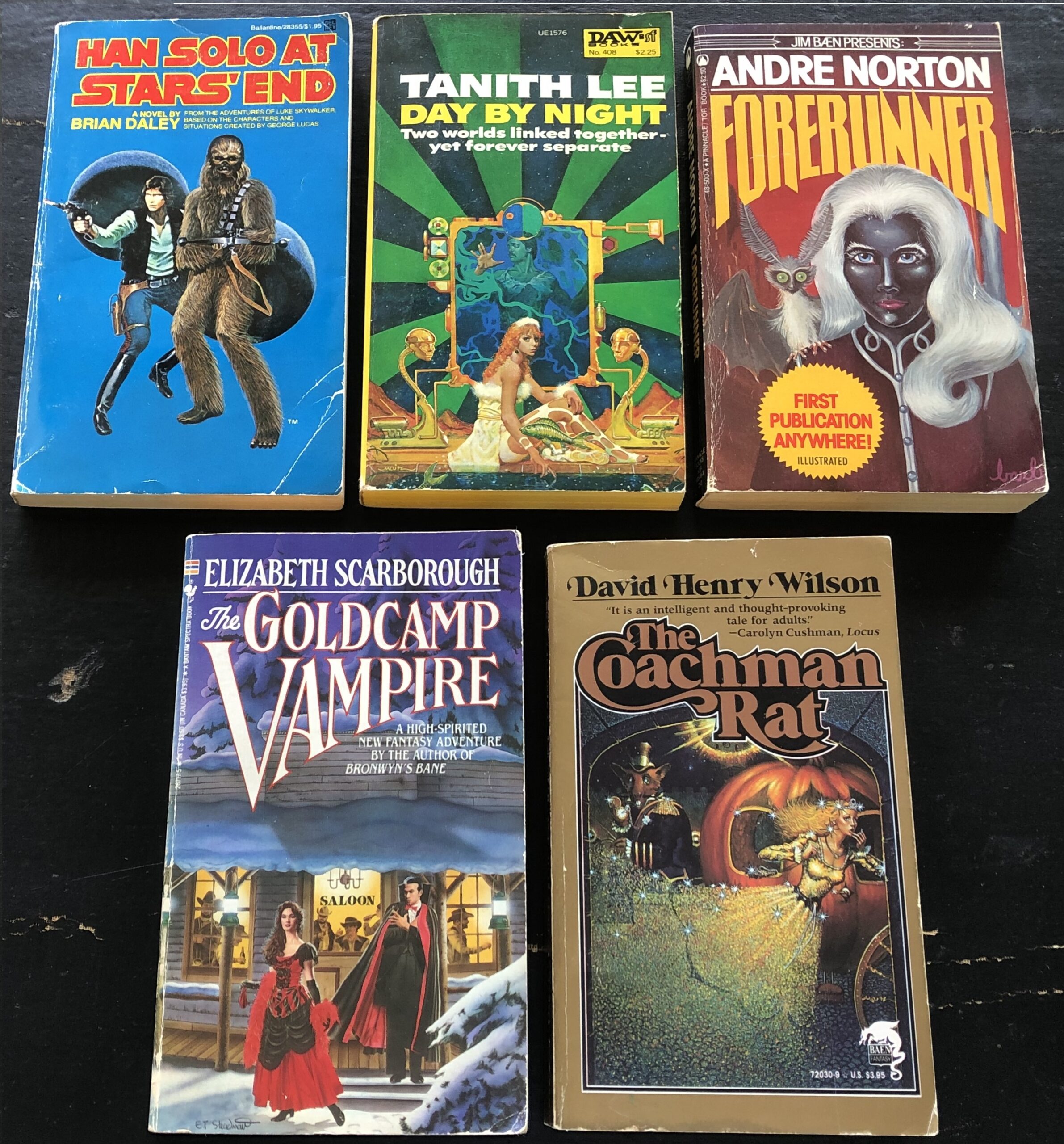

Paperback imprints specializing in science fiction and fantasy continued to expand. DAW (1971), started by Donald A. Wollheim and Elsie B. Wollheim, was the first US paperback line to begin as exclusively a fantasy and science fiction house.

Harlequin returned to science fiction with Laser Books in 1975. They published 58 paperbacks, including early works of Tim Powers, before shutting down the imprint in 1977.

Del Rey (1977) was more successfully spun off Ballantine as a science fiction and fantasy imprint under the editorial direction of Judy-Lynn del Rey and Lester del Rey, publishing the original Star Wars novels and more. Tor (1980) and Baen Books, started in 1983 by one of the Tor founders, Jim Baen, featured both established and new authors in the genre. Bantam Spectra (1985) emphasized original fantasy and science fiction.

Ebook Competition and the Future of Paperbacks

Harlequin eventually returned to the fantasy market in the early 2000s with imprints such as Luna and Nocturne Bites. These included trade paperbacks and ebooks, marking a shift away from the mass market paperback format by the world’s largest paperback publisher.

Still, at the start of this century, paperbacks were available for purchase everywhere. While prices rose, the books remained affordable and easily portable reading material, perfect for a commute or enjoyment at home, just as Lane envisioned in 1935.

However, as we celebrate nine decades of mass market paperback, publishers are beginning to abandon the format.

A new cheap way to consume popular fiction, the ebook, cut into mass market paperback sales. By the 2010s, the Kindle, Nook, and Kobo devices dropped in price. Reading a book on a mobile phone or tablet became popular. All of these inventions made it possible for readers to carry literally hundreds of ebooks on a trip in the same space as a single paperback.

Trade paperbacks, 8 ½ inches tall and 5 ½ inches wide, became an economical and good-looking print alternative to hardcovers for producers and consumers. With the availability of quality print-on-demand machines set up for this format, the attractiveness of mass market paperbacks diminished for the industry.

Recently, the news has been full of articles about retailers, distributors, and publishers forsaking the mass market paperback format. While it may never disappear totally, it might enter the category of “cool old stuff” like vinyl records, reproduced largely as a nostalgia buy for those of us who grew up wanting to be paperback writers.

Explore more articles from THE HISTORY FILES

Rosemary Jones had her first two fantasy novels issued as mass market paperbacks by Wizards of the Coast. The print editions of her four novels for the Arkham Horror line were all formatted as trade paperbacks by Aconyte. She also wrote several guides on collecting books published in softcover, hardcover, and ebook over the years. Always fascinated by changing fashions in how books look, Rosemary lives with more than 2,000 books bought for reading and research. More information about her writing and collecting adventures can be found at rosemaryjones.com. You can see books from her collection on Instagram at lost_loves_books.

Rosemary Jones had her first two fantasy novels issued as mass market paperbacks by Wizards of the Coast. The print editions of her four novels for the Arkham Horror line were all formatted as trade paperbacks by Aconyte. She also wrote several guides on collecting books published in softcover, hardcover, and ebook over the years. Always fascinated by changing fashions in how books look, Rosemary lives with more than 2,000 books bought for reading and research. More information about her writing and collecting adventures can be found at rosemaryjones.com. You can see books from her collection on Instagram at lost_loves_books.