Key Conditions for Suspense:

Part 14 – Put Your Plot Together with the Story Cycle

by John D. Brown

The following is part of a continuing series. If you wish to start at the beginning, head to It’s All About The Reader.

The following is part of a continuing series. If you wish to start at the beginning, head to It’s All About The Reader.

It’s good to know you need to make the problem hard to solve, but how do you use all the obstacles to develop the plot? How do you layer them in? How do you start and move forward?

You follow the story cycle, which is simply a model of how we humans go about solving problems, and apply the techniques we’ve been talking about in ways that make sense to you and spark your interest. You can move forwards or backwards around the cycle, whatever is most productive to you at the time.

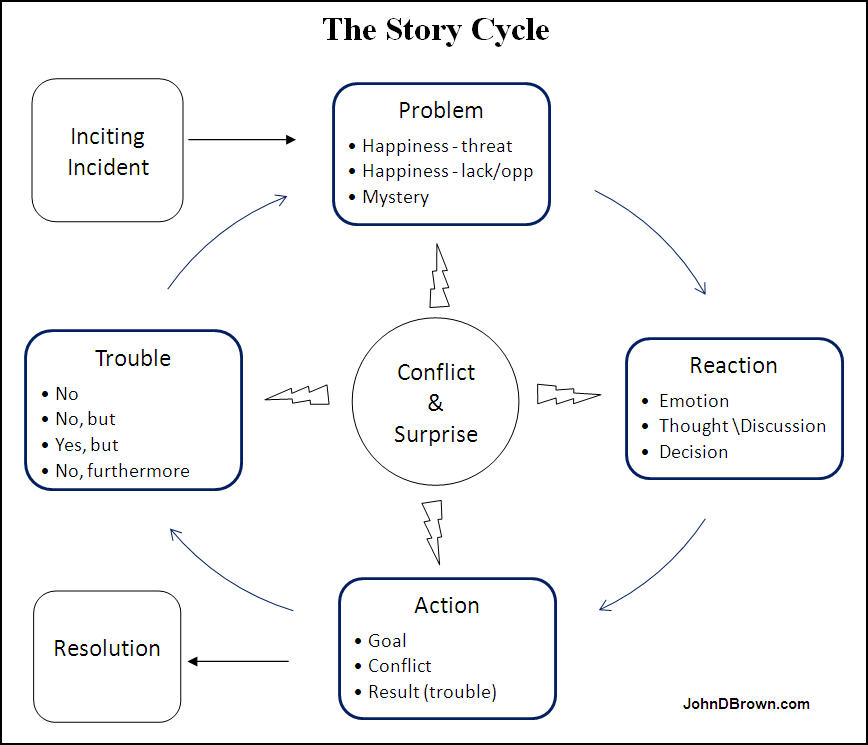

I’ve inserted a diagram of the cycle below and will explain each element in the next three posts. Please note that this is built on the wonderful discussions of scene and sequel found in Dwight Swain’s Techniques of the Selling Writer and Jack Bickham’s Writing and Selling Your Novel and Scene & Structure. I’ve added my own insights, but if you want an expanded discussion of this topic, you might want to read what they have to say there.

One thing to note before we dive in is that the parts of the cycle don’t always correspond to individual scenes on the page. You can present an action or reaction in a scene, a sequence of scenes, narrative summary, or, if it’s insignificant, you might not present it at all. The decision about what to put into scene, narrative summary, or leave out entirely is an important question. For right now, just know that story is about a character’s attempts to solve a problem and the results of those attempts and you’ll want to share the actions and reactions that make a difference.

So let’s get to it. In this post, I’ll discuss the inciting incident and the reaction. In the next post, I’ll discuss action and the all important trouble. In the post after that, I’ll explain the dynamo that makes the whole thing go around—conflict and surprise.

Inciting Incident

Everything starts at the point when the problem arises for the lead character. In fiction, we call this the inciting incident because it’s the incident that puts everything in motion. In real life, it’s the “ah, crap” or “oh, no!” moment. Or, if this is a story about a lack/opportunity, it’s the moment of “dude!” and “oh-my-gosh, oh-my-gosh!”

So with a murder mystery, this is the point in time when the lead character learns about the murder. We might see that murder in an opening scene, but they story doesn’t start until our lead gets involved. In a story about a kidnapping, it’s the moment when grandma is shoved into the back of the van. In a love story, it’s the moment when the girl meets the boy.

There are variations to how it’s presented. In some stories, it’s the lead character whose actions initiate this event. In other stories, the lead character is minding her own business or on her way to doing something else, and the problem finds her. Some stories might start with the inciting incident of the central problem and then the inciting incident of a subplot. Other stories switch the order. Still others present a number at the same time. Some problems are presented quickly. Others are presented over a few scenes.

All the variations work. The key is that the story doesn’t start until this incident is presented to the reader because it’s this incident that raises possibilities that allow the reader to worry.

There will be changes, complications, and developments in the central problem as we go along. We don’t need to know everything about the problem in the beginning. We just need to know that the character has a problem.

Reaction

So what do we do in normal life when presented with a problem? Let’s say water starts dripping out of the light fixture right above your kitchen table. Maybe the wiring in the light starts to spark. What do you do?

First, you will experience some emotional response. It might be alarm (Crap! That might start a fire!), or anger (Those morons who rent upstairs!).

Next, you consider your options. You can put a towel or bucket under the fixture. You can go bang on the door of the apartment above. But maybe the people are gone, so you’ll have to break in a window or try to force the door, or call the apartment manager. Maybe you can call your buddy who is in construction. Depending on the problem, you might find yourself in a discussion, performing some analysis or research, or sketching out a plan. Or maybe you need to act immediately and don’t have much time to plan the best approach.

However long the time of consideration, at some point you must decide on a course of action.

So there’s an emotional reaction, thought, maybe some discussion, and then a decision. When we face any problem in real life, we follow that same sequence:

• Emotion

• Thought

• Decision

For our plot to feel real, we need to follow that sequence with our characters as well. Very often this is the time when stakes and plans are shared with the reader. And all of those raise good and bad possibilities in the mind of the reader. Things for them to worry about.

The reaction is a great time to explore motive, which affects a reader’s sympathies. It’s also a great time to explore things in the character’s past.

Sometimes in real life we move through the reaction process quickly. Sometimes it takes a while. This happens in a story as well. But because you want to make things clear, you’ll remember that any non-standard decision will need an explanation. So you’ll put that into the thought or discussion part so it makes sense to the reader.

When the character finally arrives at a decision, the reaction phase ends. Usually, because that decision is to take some action that’s meant to resolve the issue. But even if the character decides to ignore the problem, that’s an action. And as you’ll see, it’s going to fail. Because plot is all about trouble. And that’s what I’ll discuss in the next post.

Happiness,

John

•••

John Brown is an award-winning novelist and short story writer. Servant of a Dark God, the first book in his epic fantasy series, was published by Tor Books and is now out in paperback. Forthcoming novels in the series include Curse of a Dark God and Dark God’s Glory. He currently lives with his wife and four daughters in the hinterlands of Utah where one encounters much fresh air, many good-hearted ranchers, and an occasional wolf.

John Brown is an award-winning novelist and short story writer. Servant of a Dark God, the first book in his epic fantasy series, was published by Tor Books and is now out in paperback. Forthcoming novels in the series include Curse of a Dark God and Dark God’s Glory. He currently lives with his wife and four daughters in the hinterlands of Utah where one encounters much fresh air, many good-hearted ranchers, and an occasional wolf.

For a list of all of the posts in this series thus far, click on the “John D. Brown” tag.