Guest Post: Playing with Structure

by Christie Yant

The following article was originally posted on Inkpunks.com, a blog for new, nearly new, and newly pro writers.

The following article was originally posted on Inkpunks.com, a blog for new, nearly new, and newly pro writers.

Okay, so I’m probably a total freak, but I love structure. This is what gets me through first drafts (which I loathe). It’s what makes a nebulous idea sort itself out in my head. There are some wonderful books on structure out there, and I’d advise you to heed the wise words of writers much more skilled than I–but because I’m having so much fun with it right now, I thought I’d talk about how I apply it.

My first experience with actively applying a structure to a story happened two years ago (many years into my journey as a writer). I had this work in progress that wasn’t quite coming together. It’s a story in two worlds, with two completely different voices. One world was primary, the other was secondary, but they were both essential to telling the story. The primary world needed more words, more time, more attention. The secondary world needed to be terse, fast–only the essential information, so that the reader didn’t get lost in that world before they returned to this one. So I took the draft, printed it out, cut it up, and looked at how long each of those sections was, and then edited it down until it fit a structure that looks something like what follows. (In the examples below I’m using – and * to indicate subject matter, POV, or themes that differ from each other. # designates a scene break.)

------------------ -------------- ----------- # ****************** ***************** ***************** ****************** # ----------------------------- ------------------------------- ---------------------------------- ------------------------------ ---------------------------- # ****************** ***************** ***************** ****************** # ----------------------------- ------------------------------- ---------------------------------- ------------------------------ ---------------------------- # ******* **** *** ##

I may be missing a couple of scenes there, but that’s basically “The Magician and the Maid and Other Stories” in visual terms. It sold to the first market I sent it to, and I truly believe that the reason it worked was because I imposed a structure on it.

Since then, it’s become almost a game for me. I get an idea, maybe write a paragraph, and before I do anything else I decide on a structure, and then write to it.

So: I picture the shape of the story. First thing: it’s symmetrical (mostly). I’m pretty sure you could do an asymmetrical story, but I’m not skilled enough for that yet (but gods, now that I’ve said it, I want to do it and pull it off). There’s a rhythm to it. Humans are pattern-seeking animals. We respond to that kind of thing. We respond to rhyme, and rhythm, and shape.

Once I have that decided, I can proceed. I usually have a word count in mind at this point, too. Here’s “This is Not a Metaphor” (currently sitting in a slush pile somewhere). I wanted this one to be between 1000 and 1200 words (it ended up right at 1200). In this one, the narrator is speaking to someone specific about the present in the first and last sections, and more generally about the past in the two middle sections:

--------------- --------------- --------------- --------------- # ************* ************* ************* ************* # ************* ************* ************* ************* # -------------- -------------- -------------- -------------- --- ##

Visualizing that helped me to keep my tenses and themes straight, which for me is tough even at such a short length. It helped me to pace the story, too, because I knew I needed to spend a little more time on the first and fourth sections, and less in the middle, and with a constrained word count I knew how much information I needed to pack into each.

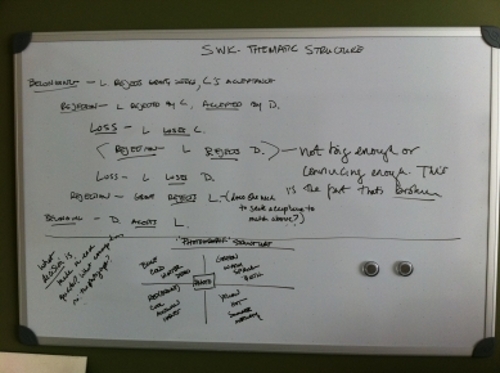

I recently dusted off an old story and decided to rewrite it from the ground up. The new elements I added in the rewrite threw the rhythm of it off completely, and I lost a couple of the thematic threads. I needed to figure out how to bring it all back together again and make sure that the themes run true, all the way through, so that’s it’s satisfying in the end. I settled on html-like tags because it made the most sense to me. This is less about the length of the scenes that it is about the thematic undercurrent that needs to run through them, but to my mind, it’s structure all the same (on my white board they’re in normal angle brackets but WordPress doesn’t like it, so I’ll use square brackets here):

[BELONGING] L. rejects G., seeks C.'s acceptance [/BELONGING]

[REJECTION] L. rejected by C.[/REJECTION]

[ACCEPTANCE] L. accepted by D. [/ACCEPTANCE]

[LOSS] L. loses C. [/LOSS]

[REJECTION] L. rejects D. [/REJECTION]

[LOSS] L. loses D. [/LOSS]

[ACCEPTANCE] ??? [/ACCEPTANCE]

[REJECTION] G. rejects L. [/REJECTION]

[BELONGING] D. accepts L. [/BELONGING]

Here’s another work in progress. In this one I’m applying structure to a story told from four different points of view. The characters have their own specific experiences, but they have one thing in common. I want the four scenes to be of equal length, with each character reaching conclusions specific to their experience and POV:

xxx 000 | yyy 111

|

a3 z2

--------------------- -------------------

y1 x0

zzz 222 | aaa 333

|

It helps me to make it visual in this way. Honestly, I blame my early aspirations toward writing comics–I often think in panels and panel layouts. I think the same principle is at work here.

I’ve been told by highly skilled writers that this is a good exercise–something to do for now, but eventually I’ll grow out of this once I internalize it. I believe them! I really do. The thing is, I keep discovering different structures to try, and I can’t see myself internalizing any of them until I run out of new ones. In conversation with Jaym I decided my next project needs to be based on a Venn diagram. Who’s to say that won’t work superbly?

Here’s one I haven’t tried. Maybe we could make it a challenge.

- -- --- ---- -----

Now I’ll be up all night trying to figure out how to write a story like that.

Oh wait. Never mind. I think I just got it. (Seriously, I think I just need one of those toddler shape-sorting toys, and I could write happily forever.)

Maybe I really will internalize all of this, and the whole process will shift for me–maybe I’ll think of a character first, and then a situation, and then the structure will naturally fall out of that. I’m open to that possibility. But for now, this is what’s working for me–but I think that’s because it’s what’s most interesting to me. Of course the real key to writing a successful story is to write what’s most interesting to you, be it a structure, a character, a voice, a theme, a plot, a pace, or a setting.

A good story requires all of that, but where you start is up to you. I’ll be starting at the white board–at least for now.

•••

Christie Yant is a science fiction and fantasy writer, Assistant Editor for Lightspeed Magazine, occasional narrator for StarShipSofa, and co-blogger at Inkpunks.com, a website for new, nearly new, and newly-pro writers. Her fiction can be found in the magazine Crossed Genres and the anthologies The Way of the Wizard and Year’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2011, both from Prime Books. She lives on the central coast of California with her two amazing daughters, her husband, and assorted four-legged nuisances. Follow her on Twitter @inkhaven.