Key Conditions for Suspense:

Part 16 – The Story Cycle’s Dynamo (and a little Hitchcock)

by John D. Brown

The following is part of a continuing series. If you wish to start at the beginning, head to It’s All About The Reader.

The following is part of a continuing series. If you wish to start at the beginning, head to It’s All About The Reader.

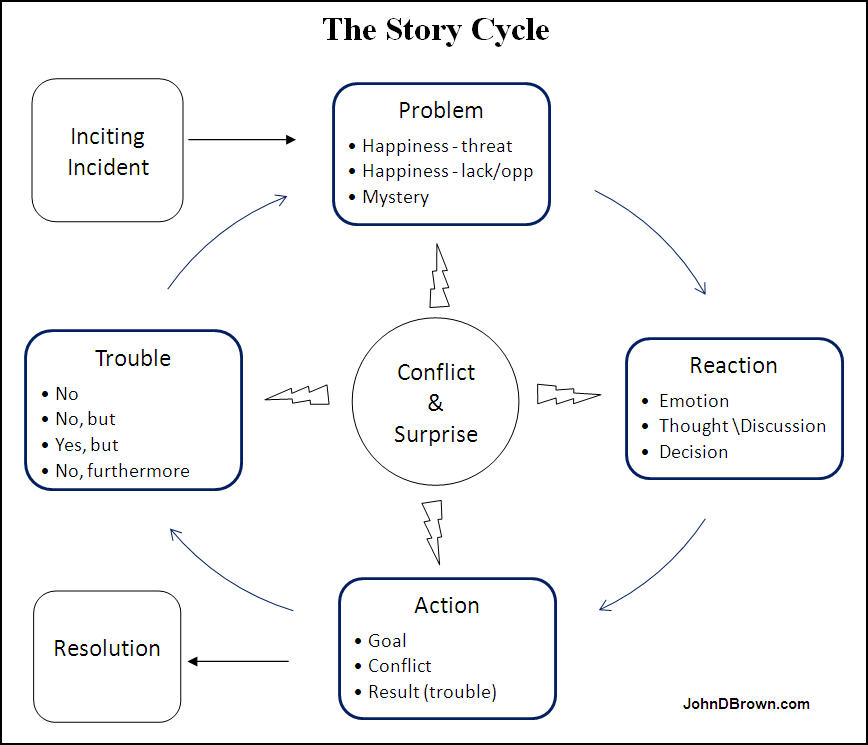

Conflict and Surprise

Let’s look at the story cycle again. You’ll notice I’ve drawn the graphic with conflict and surprise as the dynamo in the middle that gives energy to the wheel. The role of conflict and surprise cannot be overstated. They imbue every part.

The inciting incident leads the character smack into conflict and surprise.

The action revolves around obstacles and conflicts and surprises. More importantly, it ends in a great dose of conflict and surprise—that’s the very definition of a yes-but and a no-furthermore. The hero starts out thinking his action will work and finds it doesn’t. Surprise!

Even in the reaction stage we can include conflict and surprise. Maybe after our team’s setback, they regroup and discuss what they’re going to do now. This is a fine time to allow the varying motives of those on the hero’s team conflict. Maybe this is the time when one of the people we rely on defects to the other side. Maybe it’s the time when we begin to really see the impact of the disaster that just occurred. It’s also a wonderful time for our hero to come to a surprising insight or make a surprising but logical decision. Or let one of the other characters make a surprising suggestion.

Through it all, this conflict and surprise keep the character at a disadvantage. And that keeps the reader hoping and fearing and wondering what in the world will come next and how will the character ever pull it off.

Look for how conflict and surprise work in the stories you love. And if you’d like, you can see it work in a fabulous sequence in Life, season 1, episode 3.

Charlie Crews is a detective who was sent to jail for a murder he didn’t commit. Being a cop in prison made him a target for many beatings, hence the yellow coloring on his face in the image you see below.

Eleven years later investigators found that none of the DNA at the murder site was his. So they released him, and, as settlement for damages, gave him a bunch of money. More importantly, they allowed him to be a cop again. Even more important: it might have been a cop who set him up. He’s been partnered up with Dani Reese. Nobody really wanted him, but she’s had problems of her own and got stuck with him. (Anyone want to say Holy Multiple Points of Conflict, Batman!)

In this sequence I want you to watch, Crews and Reese are looking for a guy named Manny Umaga who carjacked a man and his wife then shot the wife.

Watch it and then read my comments below. The sequence in question runs from minute 15:49 to 21:15.

(Here’s a direct link in case you’re having trouble viewing the video above.)

1. Surprise. You walk into a dangerous car shop. What are you expecting? You know you’re going to meet hard characters. They’re not going to want to talk to you. There’s some danger here and, therefore, a bit of suspense. So we meet some hard characters. But did you see the surprising particulars of Buscando Maldito–his neck tattoos and hat? Wonderful. Not totally surprising, but particular for sure. Then before we can have the expected confrontation–surprise–Crews sees the car of his dreams. Then we get that wonderful exchange between him and Maldito and El Repitito. Total humor. Totally unexpected. Next Maldito suggests a posse? Not only is he willing to talk, but he suggests he goes with them? Another surprise! Did you notice as well Maldito’s surprising responses to Reese’s questions—no on-the-nose dialogue here. When going to get Umaga, more surprises. Flash bangs? Big honking Samoan running like that? Busts down the door? Takes Crews by the neck? Crews pulls his own knife? Surprise after surprise after surprise.

2. Conflict. Between Crews/Reese and guys in shop, Maldito and Crews about the car, Maldito and Reese (didn’t you love that bit about the airbrush), between Umaga and Crews, between Crews and setting. Then Crews and Reese (with the knife). Go back to the post on making plots hard to solve with conflict if you need to review.

BTW, look at this sequence with the lens of the story cycle. If you watch just a little bit more, you’ll see it’s a classic yes-but trouble. Yes, they find Umaga (not without a lot of conflict), but the victim won’t identify him as the killer. And around the cycle the story goes again.

Now look at the last few scenes in the current story you’re reading. Is the author using conflict and surprise as tools to move the story around the cycle?

Plots that rock

We present readers with sympathetic and interesting characters who are dealing with significant hardships or dangers. But readers don’t want to worry for two seconds and then have their tensions resolved. They want to feel a rush of relief. And you can’t feel a rush unless there’s something major to feel relief from.

When does cold sweet water taste the very best?

Not when you’ve just drunk a gallon jug of it. Not when you’re swimming in a freezing lake full of it. No, water is mind-blowing when you’re so thirsty your tongue cleaves to the roof of your mouth, when the spittle has dried all around your lips, when you’ve been thinking about that drink for hours and the world seems to be nothing but heat and rock and dust.

When you’re bone thirsty dry, that’s when the first sip feels like the rapture.

The magnitude of the relief experienced in the resolution is in direct proportion to the stress that comes before it. So the more tense the reader is when they get to the resolution, the bigger the relief. If you’re delivering a mystery, the more puzzled the reader is, the bigger the insight.

In the beginning of the story we introduce the problem, raising a reader’s curiosity and interest. In the end we resolve the problem and satisfy the reader’s thirst. But it’s the wonderful middle where we build the thirst. With great middles, our story resolutions bang. Without them, they ho-hum and fizzle.

And it all revolves around making the story problem harder to solve. In fact, I’ve found that as long as I keep thinking about how to keep making things harder on my characters, the story scenes seem to line up and present themselves.

Now, we’re not done with plot just yet. In the next ten or so posts, I’ll discuss the big picture of plot. It’s called structure. I’ll share why I think it’s more helpful to think about structure in the context of problem-solving, plot patterns, and Pareto elements than it is to talk about mythic journeys or rigid act numbers, proportions, and plot points. I’ll also break down at least one novel so we can see how an example of how everything we talked about works in practice.

In the meantime, if you think you might see other things that make a problem harder to solve or affect the story cycle, please add them in the comments.

Bonus 1 – A little Mr. H.

The following is an excerpt of an interview, presented in two parts below, between Alfred Hitchcock and Huw Wheldon. It was filmed for the BBC television program “Monitor” and was first broadcast on May 5, 1964. Watch it, keeping in mind the points made above. Of course, the purpose of sharing this isn’t to quote it like scripture. We don’t want to accept anyone’s model of story without thinking about it and testing it against our experience and observations. So listen and then let me know if you think his ideas are accurate.

Part 1

(Here’s a direct link in case you’re having trouble viewing part 1 of the video above.)

Part 2

(Here’s a direct link in case you’re having trouble viewing part 2 of the video above.)

Here’s another. In “Movie Go Round,” recorded in 8 July 1966 for Light Programme, Alfred Hitchcock talks to John Kennedy about the enjoyment of fear & ways of creating suspense (with reference to Vertigo).

By the way, if you enjoy Hitchcock, you’ll want to read Hitchcock on Hitchcock: Selected Writings and Interviews, edited by Sidney Gottlieb.

Bonus 2 – Development Questions

You can start trying to apply the Pareto factors that have been discussed right now. Here are examples of productive questions you can ask yourself.

Problem

- What types of danger might my character face?

- Who’s in the most danger?

- Who stands to lose the most?

- What’s a stake?

- What are the character’s opportunities?

- What kinds of hardship might they face now?

- What are some potential mysteries in this world or with this problem?

- How can I make the problems more intense?

- Who might cause a lot of trouble in this situation?

- Why would the opposition want what they do?

Character

- What are some things that could make my character sympathetic?

- What are some things that could make my character deserving?

- What are some things that could make my character more interesting?

- What are some ways I could provide cast variety?

- Why types of people would be fun to put together?

Plot

- What types of obstacles does the character face?

- What are some things that can put my character at a disadvantage?

- What are some possible fun points of conflict inside the character, with people on the character’s team, with the opposition, and with other bit parts?

- What are some possible upsets the character can experience along the way?

- In what ways might the problem get worse?

- What are some surprises I can spring on my reader and character?

You don’t need to answer every question. Just take one and run with it listing as many options as you can. List out all the dumb clichés that come to mind. Don’t filter yourself. You must practice farmer’s faith when you write. Farmers throw manure on their fields because it makes things grow. Dumb stuff works like manure. Spread it around in the garden of your mind and watch the flowers grow. As you generate your options, go for quantity, try to vary the nature of the solutions you come up, and try to think up some that are unusual. Sooner or later you’ll start coming up with ideas that spark.

Bonus 3

I don’t want you to simply accept the model of the story cycle I’ve presented above. Please take some time when you next watch a TV episode or movie or read a novel and see if and how it works in the kind of fiction you love. You don’t have to break down the whole story if you don’t want to. Just do a scene or three. Then report back here what you found. You, me, and everyone who reads this will be better for your insights.

Happiness,

John

•••

John Brown is an award-winning novelist and short story writer. Servant of a Dark God, the first book in his epic fantasy series, was published by Tor Books and is now out in paperback. Forthcoming novels in the series include Curse of a Dark God and Dark God’s Glory. He currently lives with his wife and four daughters in the hinterlands of Utah where one encounters much fresh air, many good-hearted ranchers, and an occasional wolf.

John Brown is an award-winning novelist and short story writer. Servant of a Dark God, the first book in his epic fantasy series, was published by Tor Books and is now out in paperback. Forthcoming novels in the series include Curse of a Dark God and Dark God’s Glory. He currently lives with his wife and four daughters in the hinterlands of Utah where one encounters much fresh air, many good-hearted ranchers, and an occasional wolf.

For a list of all of the posts in this series thus far, click on the “John D. Brown” tag.