Translating the Hero’s Journey Into a Linear Plan

by Susan Forest

There are as many paths into creating fiction as there are writers, and widely differing approaches have led to successful works. Entire books have been written how to plan a story; here, I will focus on one small process: translating the circular Hero’s Journey into a linear plot.

There are as many paths into creating fiction as there are writers, and widely differing approaches have led to successful works. Entire books have been written how to plan a story; here, I will focus on one small process: translating the circular Hero’s Journey into a linear plot.

This translation involves (1) considering the change arcs of each important character, (2) ensuring the obstacles and the choices the character makes are linked in a logic chain, (3) coordinating each character’s effect on the events, and (4) ordering the resulting scenes into a single list.

Consider the change arcs of each important character

Because the events showing your protagonist’s Hero’s Journey may already demonstrate a well-defined arc, it is tempting to stop planning and start writing, even though the plan may seem thin and obvious: the novel that should run 100,000 words looks like it might only be 20,000. If you stop here, you may face a “muddle in the middle,” caused by not fully understanding the actions and motivations of all key characters.

“Act II belongs to the antagonist.” Why? Because the antagonist is your story’s engine, a character who, like your protagonist, wants something very badly and acts strongly to get it. It is because of the antagonist that the protagonist has obstacles to overcome. So: consider the hero’s journey from the antagonist’s point of view, ensuring you have one or more scenes to show her progression. If the protagonist and antagonist are in the same scenes, this stage may show a duplication. That’s fine.

Do the same for each important character. In the course of creating Heroes’ Journeys for mentors, sidekicks, and minions, you will discover a multitude of little “aha!” moments, such as how one character’s journey creates insight in your protagonist’s life, or how you had envisioned an important character’s first Act, but never completed her story.

Ensure the obstacles and the choices the character makes are linked in a logic chain

Here, tables come in handy. For each character, create a table listing her key scenes in one column (“Narrative”) and create a second column labeled “Becauses” or “Why now?” For each scene, provide the immediate reason why this character performs this action now. Do not confuse this column with “Function.” A “Function” column describes the step on the Hero’s Journey or the Obligatory Scene; it is not a story event. Here is an example:

| Function | Narrative | Why now? |

| Ordinary world | Little Red Riding Hood’s mother gives her a red hood to wear | Her mother loves her (or, because it’s her birthday) |

| Call to adventure | Red’s mother asks her to take a basket of goodies to Grandma’s house | Grandma is sick and can’t cook for herself |

| Crossing the threshold | Red skips off down the path into the forest | Red is a good and helpful child, doing what her mother asked |

Again, this step results in a plenitude of “aha!”s. You may discover some of your characters do things to satisfy your plot and are not motivated by their own internal motives. If so, go back to the drawing board and become creative. If you do this now, before you are 60,000 words into the story, you avoid a second source of frustrating “muddle in the middle.” Again, you will also discover cross-fertilizations among characters that give you greater insight into their backgrounds and reactions, and may alter the actions they take, enriching your story. New scenes may be added to some characters’ lists.

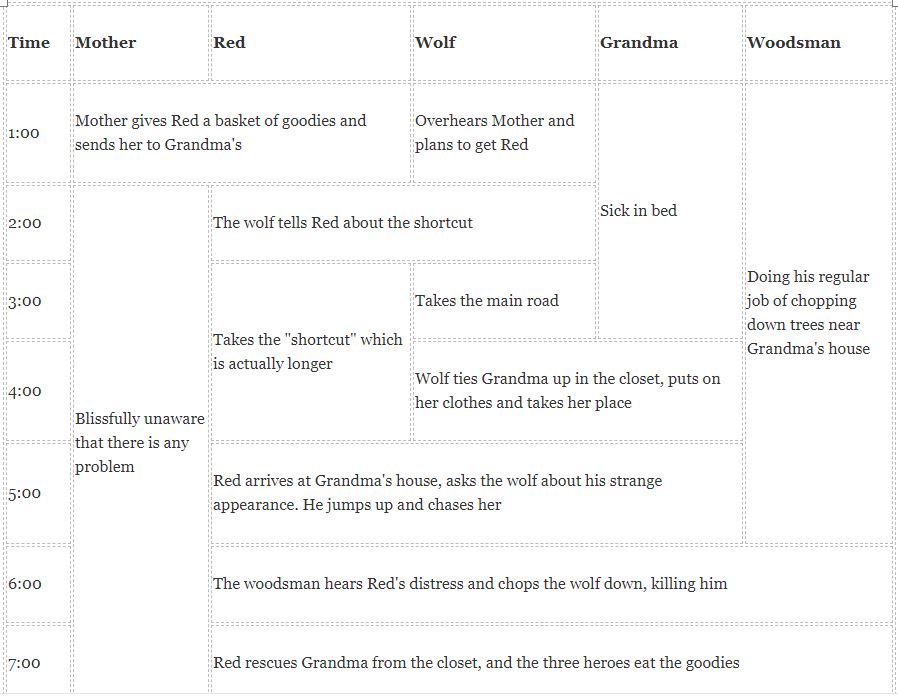

Coordinate each character’s effect on the events

Create a table with a vertical dimension of time or progression, and a horizontal dimension of characters, and fill in the actions from each character’s table. Merge cells when two or more of your characters are in the same scene. This helps you to see not only how characters interact, but what offstage characters are doing.

Clearly, some parts of this story will not be shown, such as what Mother is up to after she sends Red to Grandma’s, but it is good to know what offstage characters are doing.

Order the resulting scenes into a single list

From here, it is straightforward to create a list amalgamating all the key characters’ scenes in order. Some scenes may be moved, expanded, divided, or merged. Include the column showing all your “Becauses” (and your “Functions”), tweak, and start writing.

This may seem like a lot of work before you begin writing, and certainly this process will not appeal to every writer. However, this system can be helpful in a number of ways:

- Prevent “muddle in the middle” problems by ensuring each scene is part of a logical chain of action/reaction before you get 60,000 words into the manuscript.

- When you sit down to write, you know exactly what has to happen in that scene, why, and how it fits in the context of what comes before and after.

- You learn a lot about your characters, their motives, and how they interact. You find new actions they can take, and you enrich your story’s themes.

Finally, of course, the plan is only a road map. You still need to write the book (and be prepared to turn left at Albuquerque if the story so demands), and do all your revisions and beta tests. But if planning is something that interests you, the above steps can provide a helpful structure.

•••

Susan Forest is a writer of science fiction, fantasy, and horror and a three-time Prix Aurora Award finalist. Her novel, Bursts of Fire, the first in a seven-volume YA epic fantasy series, the Addicted to Heaven series, will be out in 2019 from Laksa Media, followed by Flights of Marigolds. She has published over 25 short stories which have appeared Asimov’s, Analog, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, and her collection, Immunity to Strange Tales, among others. Susan has co-edited three anthologies (Aurora-winning Strangers Among Us, The Sum of Us, and Shades Within Us) on social issue-related themes with Lucas K. Law. Susan is the past Secretary for the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA), teaches creative writing at the Alexandra Writers’ Centre, and has appeared at many local and international writing conventions. Susan loves travel and has been known to dictate novels from the back of her husband’s motorcycle.